Harmon’s Histories: A remarkable account of the Nez Perce War, through Native eyes

About a year ago, I wrote a piece about the 1877 Nez Perce War and how the Montana press described it as a frightening time for white settlers in Missoula and the Bitterroot Valley.

The story also included a sidebar on the petty war of words between Weekly Missoulian editor Chauncey Barbour and New Northwest editor James H. Mills over the treatment of Deer Lodge volunteers who came to Missoula to help intercept the Nez Perce at Fort Fizzle.

I wondered at the time if there might have been any Montana newspaper articles detailing the Nez Perce viewpoint of the war. It turns out there was, but I needed the help of a friend to find it.

I lunched last week with Gwen Lankford Spencer, who owns Sapphire Strategies Inc. I was her boss back when she was an entry-level journalist and the first Native American reporter in our newsroom. Together, we produced a documentary titled "Blood of the Earth," detailing the Native viewpoint on water rights negotiations with the state.

When I asked about the 1877 War – and a Native viewpoint – she gave me that wonderful, all-knowing smile and recommended a book by one of her ancestors from the McDonald side of her family tree.

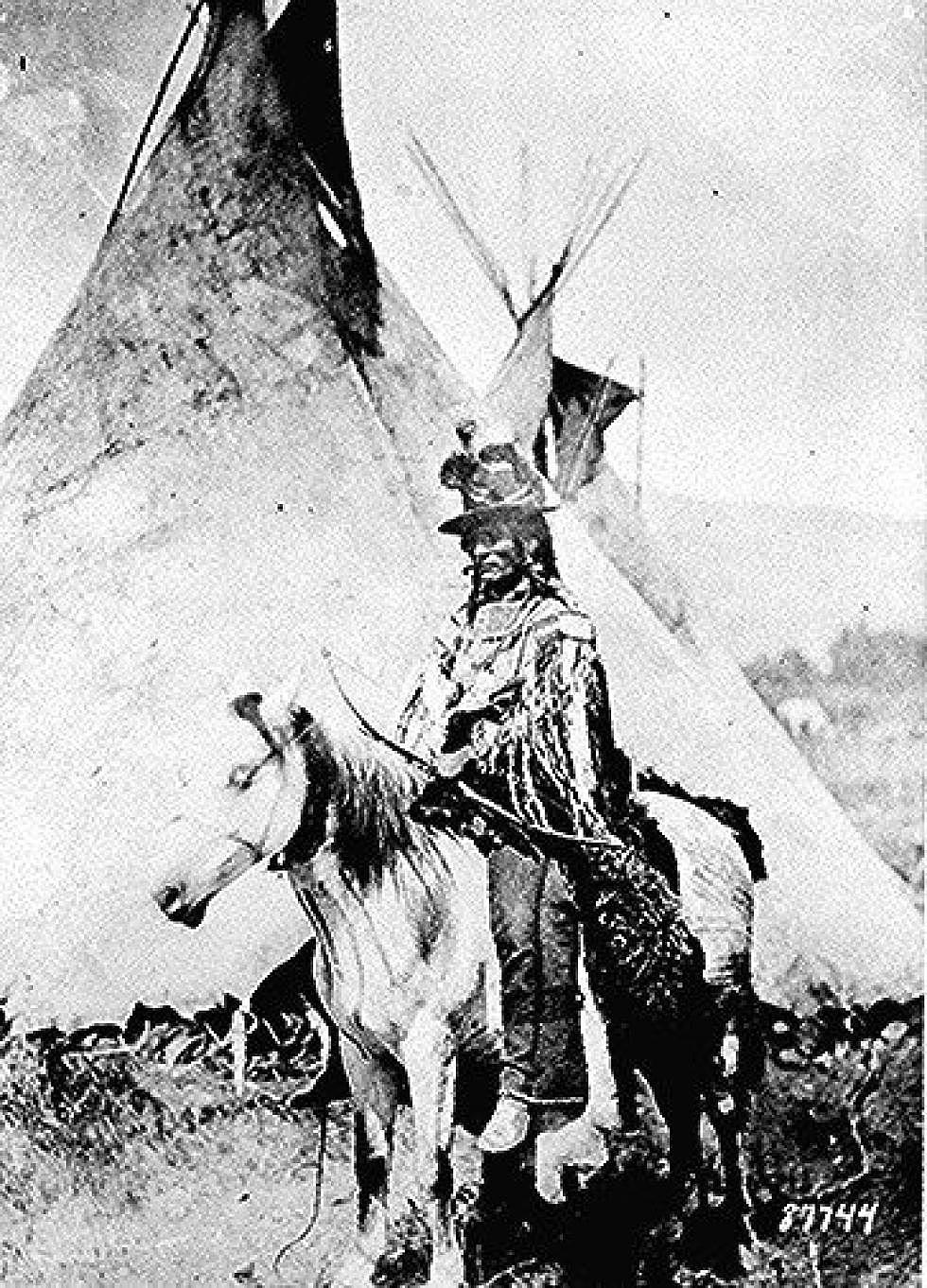

That relative, Duncan McDonald (a son of Angus McDonald, a Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader who married Catherine Baptiste, a Nez Perce woman) was related to Chief Looking Glass.

The book she recommended was "The Nez Perces: The History of Their Troubles and the Campaign of 1877." It's a compilation of McDonald's stories originally printed in serial form in the New Northwest newspaper in 1878 and 1879.

How they came to be printed is as fascinating as the stories themselves.

Almost unbelievable for the time period, James H. Mills, the newspaper's editor, actually sought out Duncan, saying "The Red Man's side of the story has not yet been told," and McDonald, "a relative of Looking Glass and White Bird... was probably the best informed upon the subject to be written up of any one in Montana."

Joseph McDonald who helped edit the 2016 book, wrote in the introduction, "For a newspaperman in 1878 Montana to seek out and support the publication of the Indian side of the 1877 Nez Perce War was remarkable."

Just as remarkable was the reaction of other newspapers of the day. The Fort Benton Record, for example, predicted the Nez Perce’s viewpoint was "more likely to be a correct version of the troubles and adventures of the tribe than were the reports of army officers who were out-generaled by Chief Joseph."

Duncan McDonald's first newspaper column, printed on April 26, 1878, detailed the tribe's "path to vengeance" triggered by numerous murders of Indians by whites who went unpunished.

"Chief Bear-Thinker was poisoned; Juliah was killed near Bozeman without cause; Taivisyact was shot while passing on horseback a house near the Missouri river," wrote McDonald. Another was killed while looking for horses, and so on.

Just before the non-treaty Nez Perce band (comprised of not only their warriors but also many women, children and elderly) left on their nearly 1,200-mile journey, General Howard met with Chief Joseph near Walla Walla.

Howard told him his people would have to move to a reservation. McDonald quotes Joseph as responding, "You say your people are too well settled to be disturbed, and I say the Indians are too well settled to be disturbed. So it is better to leave the Indians alone.

"It it our native country. It is impossible for us to leave. We have never sold our country. Here we have all we possess, and here is where we wish to remain."

Like Joseph, most Nez Perce just wanted peace – to be left alone – but a few couldn't stomach the refusal of white leaders to punish the murderers.

"Wal-litze was the man who fired the first shot in the late Nez Perce war," McDonald wrote. "He was the son of Tip-piala-natzit-kan ... who was murdered by a white man four years ago.

“Wal-litze, Tap-sis-ill-pilp and a young boy whose name is not known are the three who commenced the depredations in Idaho last summer. Both Wal-litze and Tap-sis-ill-pilp were killed in the battle of Big Hole."

As for Captain Rawn, Fort Fizzle and claims that Rawn was a coward for allowing the Indians to bypass his makeshift barriers without engaging them, McDonald asserted the Nez Perces had the highest regard for Rawn, praising him for "not opening fire on them."

In their view, "The bravest of their warriors would have done the same. Had he attacked them, he would have been severely whipped." McDonald said Chief Looking Glass made sure his warriors did not fire, clearly commanding his warriors, "Don't shoot, don't shoot. Let the white men shoot first."

Had fighting broken out on the "Lo Lo," White Bird said, "the whole country would have been fired, and many a farmer would have lost his crops and home and perhaps his scalp." It's also possible the route taken may have changed – north through Missoula and on to the Flathead.

McDonald asserted, "There were Indians on the Bitter Root and Flathead reserve who had their guns ready for use if a battle occurred at Lo Lo."

The Nez Perce accounts of the 1877 war required Duncan McDonald to conduct many interviews – even traveling to Canada to obtain Chief White Bird's version of events.

That he would go to those lengths – and that a white newspaperman would encourage the enterprise so quickly after the event – is absolutely remarkable.

Gwen summed it up best in an email to me the other day, "Can you imagine the challenge of making that journey, with children, elders, women? That part is so unbelievable to me, and reminds me that I come from strong people who have endured and persevered."

I highly recommend the book.

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula broadcaster who writes a weekly history column for Missoula Current.