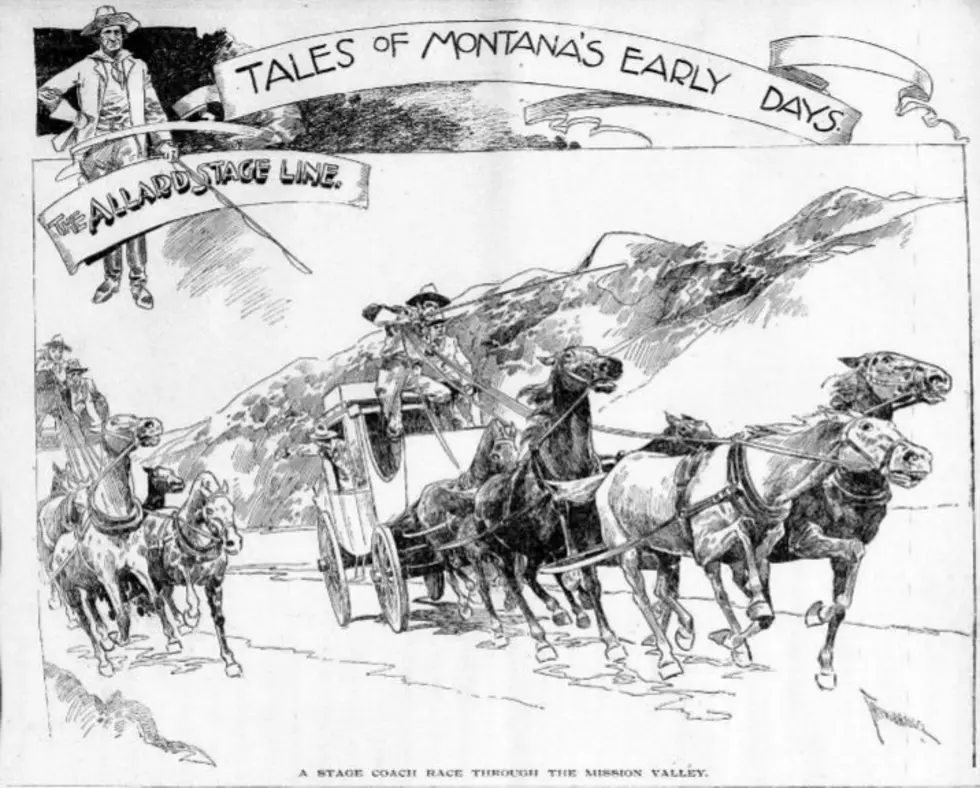

Harmon’s Histories: Climb aboard for a wild ride on the Allard Stage Line!

The stagecoach drivers knew no fear. “They drove like demons and many a timid passenger has wished that he had walked, as the line of stages tore down the hill.”

That was the Anaconda Standard newspaper’s description of what it was like to take a stage from Ravalli to the southern shore of Flathead lake in the late 1800s. Specifically, it was story about Charlie Allard’s stagecoach line.

“Old travelers across the reservation sought eagerly for seats in the Allard coaches and were disappointed if they found that they had to ride in some other.”

Drivers like Arthur Laravie, "Young Joe" Marion and Andrew Stinger were “all good reinsmen and the rivalry between them was great,” even before any other lines established competitive routes to the Flathead.

The stages “tore down the hill (above what is now Polson) that marks the end of the drive to the steamer landing. It is a long, steep slope, and it was always taken on the run. The horses knew what that hill meant and they were always ready for it.”

“They needed no urging by the drivers. They knew by experience what was in store for them and they entered fully into the spirit of the race.”

“With the heavy load behind them and no disposition on the part of the driver to use the

brake, (the horses) hit the road hard to keep out of the way of the rocking coach that swayed and swung behind them. Some passengers aboard thought the ride down the hill would be the last they would ever take, but in some way or another they always got safely to

the bottom.”

It was little different on the other end of the route, down the steep hill to the terminus of the railroad line at Ravalli.

“Arthur Laravie at one time drove his stage with its six horses for two weeks down this hill with the brake broken, so that it would not hold the wheels. He let the horses go and guided them down that steep pitch with only his sublime confidence and knowledge of the road to prevent the instant death of his passengers – for that would have been their fate had the heavy stage ever gone over the bank.”

In the early days, the Allard line had it all – the official mail contract as well as a virtual “monopoly on the passenger business.” Despite that, no one ever claimed that Allard “ever abused this privilege or extorted heavy fares from his passengers on account of the fact that he had things in his own hands,”

The “real excitement of the trip across the reservation began” when other entrepreneurs saw the opportunity to compete for passengers. At Ravalli, as a traveler would step off the train, “he was pulled and hauled about by the agents of the rival lines...it was a whirl of excitement from start to finish.”

Things escalated from there.

Soon, Allard and the other lines sent agents south to Evaro to board trains and fight it out (for customers) on the passenger cars.

When the trains arrived at Ravalli “all the stage-men had to do was to pick out the passengers that had been ticketed to them on the train.” But every now and then, a rival line would try to poach a ticketed Allard passenger, and there “would be a row!”

“The poor passenger would get the worst of it by the time agents “were through pulling and hauling him to land on the right seat and in the right stage.”

Once aboard the proper stagecoach, it was initially a slow and leisurely ride. “It was half a mile from the railway station to the top of the hill that overlooks the Mission valley. But when the top of this descent was reached there was no time lost.”

The coaches headed “down the long slope to Mission creek and across that stream on the run; then up the gradual rise to the divide between Mission and Post creeks; made another dash down the hill to the latter stream and across it, and then continued the dash over the smooth road to Crow creek.”

“Here was the racing ground. The teams of fours and sixes knew that there was work ahead for them when they started on this part of the journey. There were shouts and the crack of whips, the rattle of wheels and a cloud of dust and the race was on. It was most exciting sport.”

After crossing Crows creek and Mud creek, the Allard coaches “arrived at the Allard ranch house, where passengers were fed.”

When the stages finally arrived at the landing at the lake, “passengers and baggage were speedily transferred to the steamers. The excitement of the stage race was ended and the pleasant lake ride was ahead.”

The Anaconda Standard newspaper reported, “From the railway to the foot of the lake the road measures 34 miles. Some of the way the hills are steep and in other places the sand makes travel slow. Still these stages used to cover the distance in about three and a half hours with their heavy loads.”

But the end of an era was near.

In just a few years, the Great Northern railway completed its tracks “through Flathead county (which) destroyed the business of the stages. The steamers were taken out of service as well.”

“The drivers are now quiet farmers or stock-men whose only indulgence is an occasional horse race. The horses have gone to the last haven of all good steeds and the old stages (found tucked away in barns here and there) are the only remaining monument of the days when the stage ride across the reservation was one of the exciting incidents in Montana travel.”