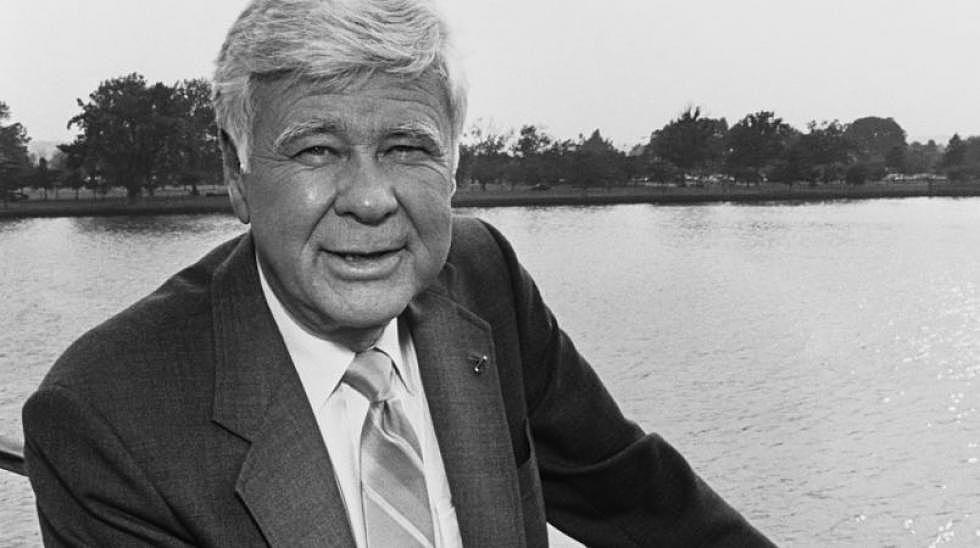

John Melcher remembered as champion of farmers, miners, ranchers, the world’s poor

Former U.S. Sen. John Melcher, who died Thursday in Missoula at age 93, was a leading congressional supporter of federal farm bills and programs to fight hunger here and around the world.

Melcher could work with the other members of Congress to get things done, but he also could be a lone wolf, when necessary, unafraid to go against his Democratic Party or the entire U.S. Senate. He served two terms in the U.S. Senate, from 1977-1989, succeeding fellow Democratic Sen. Mike Mansfield, who didn’t seek re-election in 1976.

Melcher had practiced as a veterinarian in Forsyth, where he served on the city council starting in 1953, and as mayor from 1955 to 1961. He later served as a state representative and senator before winning a special election in 1969 as Montana’s eastern district congressman. He served in the U.S. House until he was elected to the Senate.

The lone veterinarian in Congress, Melcher kept cats in his Senate office. In Montana, Melcher probably answered more to “Doc” than to “Senator. The Crow Indian Tribe gave him the name “Dull Knife.”

Melcher was a self-described political moderate, who devoted much of his congressional career to agriculture issues. He supported energy and job-creating projects like the Alaskan Pipeline and backed Montana timber, mining and oil and gas projects, but worked to pass the first federal strip-mine legislation. Melcher, who chaired the Senate’s Select Committee on Aging, sponsored bills to boost the cost-of-living formulas for retirees on Social Security.

Melcher voted for President Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts and supported a federal constitutional amendment to balance the federal budget. He opposed legalizing abortion and supported prayer in classrooms.

In 1985, Melcher kept the Senate in session until 4 a.m. to block passage of a farm bill and pushed for higher subsidies for Montana farmers, the AP reported.

Ironically, after Melcher lost for re-election in 1988, an analysis showed that voters in many of the rural counties that benefited most from his farm bills had turned on him.

Melcher was unique in how he dealt with Montana reporters. He insisted on speaking by phone to reporters who had any questions, no matter how minor, and didn’t shuffle them off on spokesmen, as most politicians do.

In 1976, Melcher won the Senate seat by defeating Republican Stanley Burger by 64 percent to 36 percent.

In 1982, the National Conservative Political Action Committee ran many TV ads contending Melcher was “too liberal” and “out-of-step” with Montanans. The same group had helped oust nine U.S. senators in 1980.

Melcher responded with the famous, or infamous, “talking cows” ad. It showed some sleazy city slickers, carrying NCPAC briefcases brimming with cash, getting off an airplane as cattle grazed in a nearby pasture. The cows, chewing their cud, talked and denounced the group’s intervention in the race. “Montanans aren’t buying it, especially those who know bull when they hear it,” one cow said.

Melcher defeated Republican Larry Williams that year, 55 percent to 42 percent.

Prior to the 1988 election, Republican Senate leaders came to Montana to recruit someone to run against Melcher, who was seen as unbeatable for re-election. Many top state GOP politicians declined. Finally, Conrad Burns, a Yellowstone County commissioner and former farm broadcaster and auctioneer, jumped in the race.

Burns suggested Melcher had lost touch with Montanans. As he traveled across eastern Montana, Burns spoke to crowds of farmers and ranchers and asked, “Anyone seen ol’ Doc lately?”

In his last couple of years in the Senate, Melcher traveled extensively to the Philippines and sponsored a number of bills to help Philippine people become U.S. citizens. He was the one of the last senators to support Philippine leaders/dictators Ferdinand Marcos and his wife and successor, Imelda Marcos. A later Philippine audit showed the Marcos family had spent many thousands dollars entertaining Melcher when he visited the country.

Burns ran a simple TV ad. It showed him standing against a wall featuring two maps, one of the Philippines and one of Montana. Burns said he would be spending his time helping Montana, not the Philippines, as Melcher had.

What likely sunk Melcher’s chances for re-election was President Ronald Reagan’s pocket veto of a wilderness bill he co-sponsored a few days before the 1988 election. The product of years of work, the bill would have permanently set aside permanently 1.4 million acres as wilderness, while releasing 4 million acres for logging, oil and gas drilling, mining and tourism, the AP said.

Burns defeated Melcher, by 52 percent to 48 percent.

Melcher later blamed his loss on his running a lousy campaign. He told the Associated Press in 2002 that he spent only 18 days on the campaign trail because he was in Washington trying to get the wilderness bill passed.

Melcher made a failed comeback attempt in 1994, losing to Jack Mudd in the Democratic primary.

For a campaign story, I was traveling with Melcher who was walking in a St. Patrick’s Day parade in Butte in 1994. To my surprise, some people along the route booed him. Few, if any, politicians had done more for Butte than Melcher.

Melcher told me how he, with the help of Senate Armed Services Chairman Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., blocked Pentagon efforts to make Butte people reimburse the government for a National Guard sky-crane helicopter. The chopper had been used to haul and set in place the six massive pieces of the Our Lady of the Rockies statue on the North Ridge in December 1985. Some federal officials objected to the use of federal money for a religious statue and demanded repayment. Goldwater and Melcher told the National Guard to call it a training mission, and the issue was dropped.

One other story about Melcher showed how he cared about people. It was in a column by Colman McCarthy of the Washington Post that told how some Catholic sisters in Washington had raised money for a day shelter for homeless women to be staffed by women. The opening of the center was set for a Sunday afternoon in 1983. All women serving in Congress were invited. So was Melcher, probably because he had a daughter who worked with homeless women in Tucson. Melcher, accompanied by his wife, Ruth, showed up. None of the female members of Congress did.

“He (Melcher) spent much of the afternoon in the living room and kitchen talking with poor women,” McCarthy wrote. “He donated money when he left, and told the Catholic sisters to call him or his staff when they needed help extracting food stamp or Social Security benefits for the women.”

McCarthy concluded: “John Melcher’s work in the Senate benefited farmers, miners, the elderly, the hungry and a constituency of the world’s poor. If all those who had been helped by him – from Washington’s homeless women to the Bangladesh starving – could have voted in Montana, he would have always run unopposed.”

Charles S. Johnson has covered Montana politics for more than 45 years and appears on the “Campaign Beat” show on Montana Public Radio. This article originally appeared on Montana Free Press.