Native historians compiling history of boarding schools

Since 2006, Denise Lajimodiere, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, has spent hours hunkered down in archives searching for records of Native American boarding schools.

“It is tedious,” she said. “It is dusty work.”

And grueling and traumatic. The records are incomplete, but what researchers like Lajimodiere have uncovered reveals a shameful history. Children were often abused, separated from their families and stripped of their culture and language. The records contain stories of both loss and resistance, but they are also important for what’s missing. Many children disappeared and never made it home.

For Lajimodiere, this work is extremely personal, and that’s one reason why she does it.

“I wasn’t sent to boarding school,” she said. “But my parents and grandparents were. My story is the story of millions of Native people and the intergenerational trauma and the historical trauma. We are still in that unresolved grief.”

The archives are scattered across the country — in government offices, church basements, historical societies and museums. Some records don’t exist at all, at least not formally. Lajimodiere, 70, found out about one school in Wisconsin only after her grandchildren went dumpster diving following the death of a 100-year-old neighbor. The woman’s family threw out many of her possessions, and the kids found an old scrapbook that mentioned a boarding school Lajimodiere had never heard of: Bethany Indian Mission in Wittenberg, Wisconsin.

To date, Lajimodiere has counted 406 boarding schools in the United States, some run by the federal government, both on and off reservations, and some run by religious organizations. In addition to identifying schools, she has also interviewed boarding school survivors and their descendants — including people in her own family — and recorded many of their stories in her book “Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors.”

Lajimodiere is one of the many Native researchers and historians who have been compiling information about boarding schools for decades. They’ve often had to advocate for the importance of their research in academia, working with limited funds. After Lajimodiere retired from North Dakota State University, where she taught, she applied for grants to continue her work in the archives, but was always denied.

The boarding school era, which ran from roughly 1879 to the 1930s — or longer depending on whom you ask — is a piece of history unknown or forgotten by many in the United States, though Native communities know it well. The federal initiative announced earlier this summer by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to look into the legacy of boarding school policies has brought sudden national attention to the issue, and for the first time, researchers like Lajimodiere and their tribes might receive significant government support and funding to continue their vital work.

Lajimodiere is one of the founders and a past president of the Minneapolis-based National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, representing tribes across the country. In 2016, the coalition filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Bureau of Indian Education to try to find out the names of all federal boarding schools and the children who died or went missing when they were students.

Their request was denied. The bureau said they didn’t have the information.

Today, the coalition is pushing Congress to pass a bill first introduced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Haaland last year to create a truth commission similar to the one in Canada that helped bring to light the history of atrocities at boarding schools there. The recent initiative announced by Haaland set a target date of April 2022 to submit a report of their findings, which the coalition believes is not enough time, considering how difficult it has been to track down documents. The commission, they hope, will continue the work.

It’s not yet clear what the federal initiative will be able to accomplish, but for Brenda Child, who is Red Lake Ojibwe and a professor of American studies and American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota, it’s vitally important to get the history right so the government can respond to it appropriately.

When Child first began her research into Native American boarding schools as a history student in the 1980s, she had to push against a lot of the scholars at the time, who argued that boarding schools weren’t very relevant after 1905. She argued that boarding schools were actually an important part of Native Americans’ lives for a few decades more, into the Great Depression and the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act. That law sought to stop the allotment of tribal land and end Native American cultural assimilation policies, including boarding schools. But Child says there’s more to the story.

“Boarding schools were about dispossessing Indians,” Child said. “By the 1930s, the big land grab was over. White Earth had lost 92% of their reservation land by then, so there’s no need for boarding schools anymore. Indians can go to public school.”

Like Lajimodiere, Child has spent hours digging through archives to find stories of boarding school students. As a history student writing her dissertation, Child was told she wouldn’t find much in the National Archives, but she went anyway and found loads of letters from students and parents. In addition to stories of loss, illness and death, she also found stories of resistance — something she finds missing in a lot of coverage of the topic today. Much of what she found is documented in her book “Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900-1940.”

A federal initiative won’t be able to return the stolen childhoods to boarding school survivors and victims. But Child says there are other things they can — and should — return to atone for the era.

“Land can be returned to Indians. The United States doesn’t have a practice of returning land to Indians, but look, we’re out there dealing with land around the Mississippi and protecting our water right now,” Child said, referring to the Native-led efforts to halt construction of the Enbridge Line 3 tar sands oil pipeline in the northern half of the state. “There’s all kinds of ways to make amends.”

Scholarships and free tuition to state universities would be another obvious way, she said.

Linda Grover, a professor emeritus of American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota-Duluth, says there is a through-line that connects the boarding school experience with Native American children’s education in public schools today.

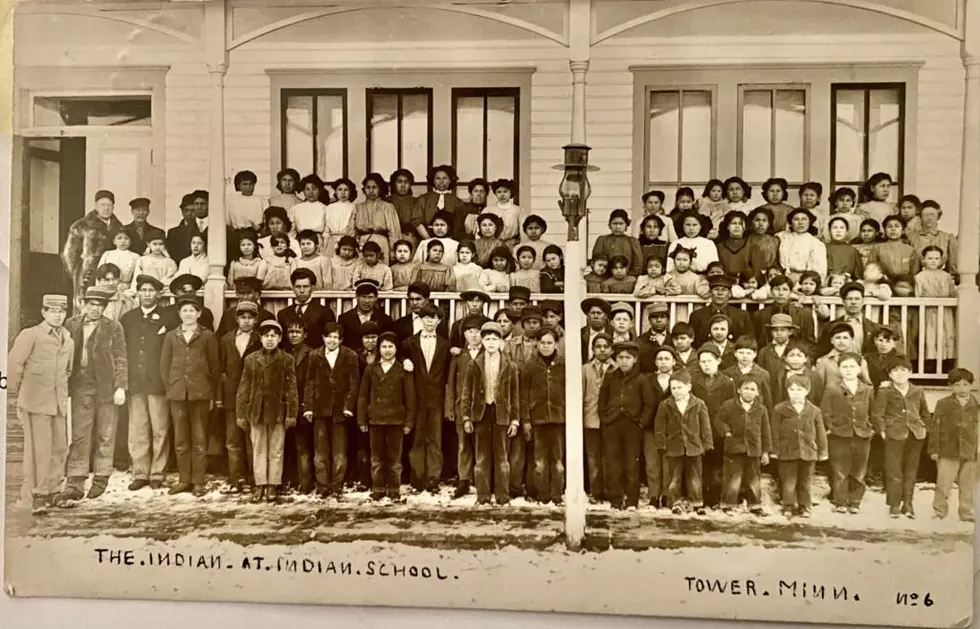

Early in her career as a historian, Grover researched and wrote about the Vermilion Lake Indian School, a federal boarding school on the Bois Forte Reservation where her grandparents met. She found that recruiters used coercion to convince parents to send their kids to the school. They would argue “the futility of efforts to continue living the Indian way.” The boys were forced to cut their hair, and all students had to wear military-style uniforms. Punishments included spanking and whipping.

Decades later, when Grover was attending graduate school at UMD, she told her aunt she was taking a history class. Her aunt responded: “Don’t let them push you out of there.”

Grover said her aunt’s generation had to fight fiercely from being excluded. “From her generation that’s how she saw things,” Grover said. “To have that feeling that this is your place as much as anybody else’s and to be really proud of who you are as a Native person is so important.”

Grover’s feeling of Native Americans being ostracized from education, however, has lingered. In the early 2000s, Grover worked as the director of Indian education for Duluth Public Schools. There, she witnessed other barriers to education for Native students. When the No Child Left Behind Act was passed, she was told they couldn’t use any of the money for educational programs connected to Native cultures.

Today, she said, things are improving. Her grandkids can learn the Ojibwe language in school if they want to. But the memories of the recent past are fresh.

One of the most lasting impacts of the boarding school era is the intergenerational trauma in families who survived. In addition to identifying boarding schools and their students, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition also works with communities to ameliorate their trauma and find a way forward. In an op-ed in The Washington Post, Haaland said this is an important part of the initiative as well: “The first step to justice is acknowledging these painful truths and gaining a full understanding of their impacts so that we can unravel the threads of trauma and injustice that linger.”

Lajimodiere hopes that part of the initiative will include sending resources and funds to tribes to pay for therapy and counseling, including from medicine people. Though she is relieved by the attention that boarding schools are finally receiving, she worries about how it might re-traumatize survivors and their families. She has personally grappled with the impact of boarding schools and understands how difficult it is to break the cycle of trauma.

“We need to research how to talk to the next generation and pass on the truth in ways that are age-appropriate and aren’t re-traumatizing, as much as possible,” she said. “We need to know about it, learn about it and understand colonialism. But it also needs to be accompanied by resilience, strength and hope.”

This story was produced by the Minnesota Reformer which is part of States Newsroom, along with the Daily Montanan. States Newsroom is a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.