Prairie Lights: In Philadelphia, a hero for our times

On my first visit to Philadelphia last week, I was overwhelmed by history.

I gawked at the Liberty Bell, stood in the hall where the founders created the Constitution, admired the house where Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and even stumbled upon a little Jewish cemetery where the honored dead included the man whose ship brought the Liberty Bell to America.

I stood in awe before the giant Washington Monument in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and I wandered through parts of the city where every corner seemed to have at least one statue of a bewigged worthy in a Colonial jacket or a tri-corner hat.

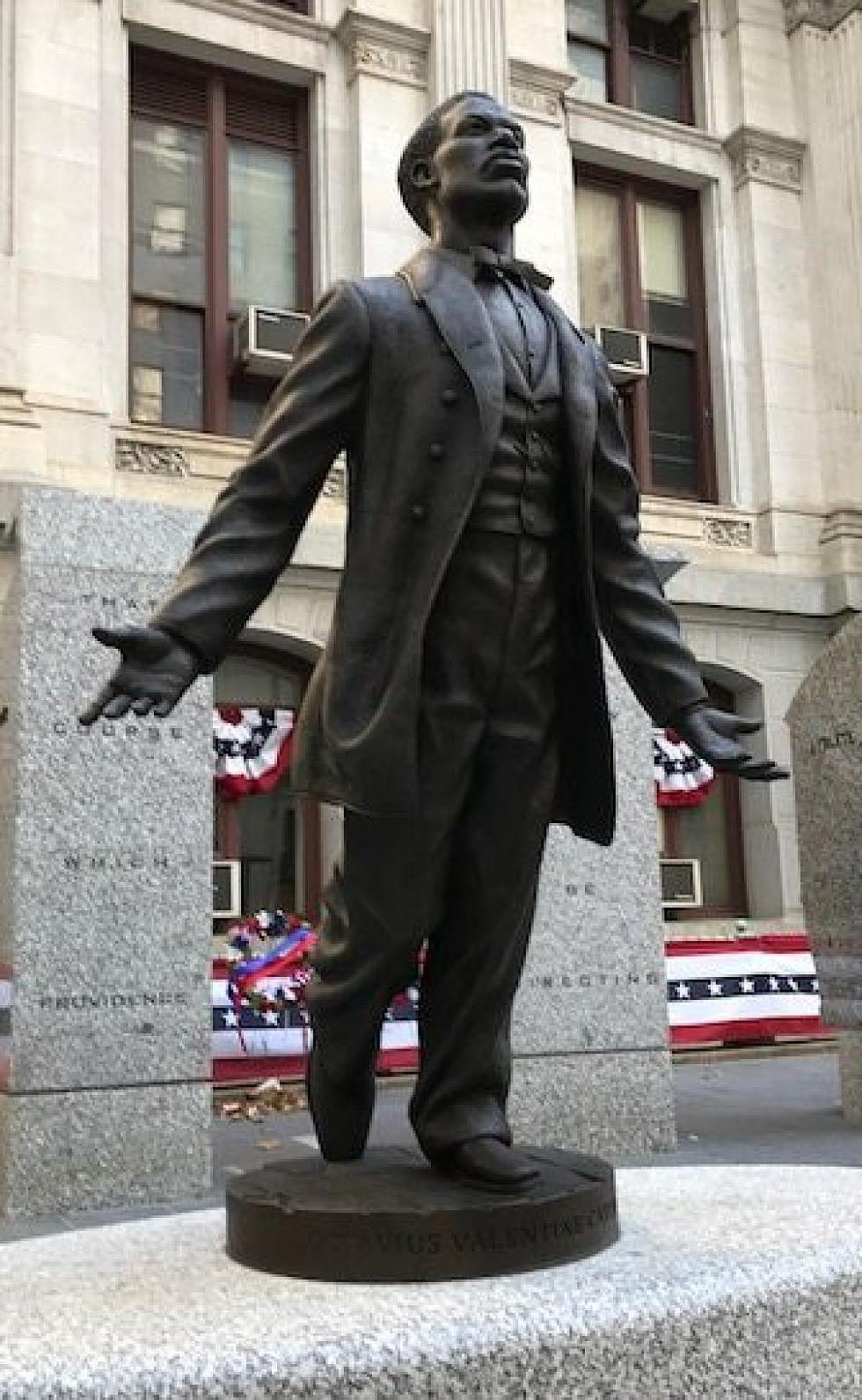

None of them, however, moved me in quite the same way as the monument to Octavius Valentine Catto on the grounds of Philadelphia City Hall.

Officially called “A Quest for Parity,” the monument was 15 years in the making and was not unveiled until late last month. It was a happy accident of timing, given the fierce debates over Confederate monuments, new questions about the meaning of patriotism and a resurgence of racism.

Catto led a remarkable life, especially considering that he was assassinated at the age of 32. Born a free black in South Carolina in 1839, Catto’s family moved to Philadelphia in 1850. Eighty years before Martin Luther King Jr., Catto led the successful fight to desegregate Philadelphia’s trolley lines, using passive resistance and demonstrations.

He worked with Frederic Douglass to recruit black soldiers to fight for the Union in the Civil War, and after the war he campaigned for passage of the 15th Amendment, which gave African-Americans the right to vote. He was also a talented shortstop who helped found the Pythian Baseball Club, and he labored to break down racial barriers in the sport.

He lived to see passage of the 15th Amendment, but on Election Day 1871, when African-Americans would finally vote, there was widespread rioting by people opposed to expanding the franchise. Catto was shot to death on the streets of Philadelphia by Frank Kelly, a Democratic Party operative.

Part of the reason that Catto’s monument was so compelling was that I had never heard of him. Neither had Mayor Jim Kenney — like Catto’s killer an Irish-American — while he was growing up in Philadelphia, and it was Kenney who began the push for the monument when he was on the Philadelphia City Council in the early 2000s.

“It’s my hope that every child in Philadelphia and America will know as much about Catto as they do about George Washington and Martin Luther King Jr.,” Kenney said at the dedication.

How much more important to know about this early crusader for basic human rights, I thought, than to see yet another monument to one of those antique patriots whose stories are so familiar that a statue seems almost beside the point. And surely it is better to learn the story of Octavius Catto than to encounter a monument celebrating a Confederate general’s contribution to a cause that deserved to be not only lost but shot dead and buried.

And if Catto’s hopes for a just society are still far from being attained, why shouldn’t his successors, in any field of endeavor, including professional football, use whatever peaceful means are at their disposal to remind us of that failure?Above all, the monument to Catto seemed painfully relevant because we find ourselves going backward again, having to contend with idiotic notions that many of us thought had been confined to a few isolated backwaters of American society.

It was amazing to learn that this Martin Luther King-like figure had been active, and partly successful, 80 years before the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott. At the same time, it has been shocking and disheartening to have a president, 60 years after Montgomery, who makes excuses for white supremacists while heedlessly playing to the basest instincts of what is called his “base.”

A monument is unlikely to change the course of history, and it’s worth pointing out that even in Philly, with its vibrant, centuries-old black culture, the Catto monument is the first one to honor a specific African-American.

But it’s a good start. We all need to honor and be reminded of the best people who came before us, especially if memories of their achievements were not only forgotten but for a long, long time actively suppressed.

Ed Kemmick has been a newspaper reporter, editor and columnist since 1980. Except for four years in his home state of Minnesota, he has spent his entire journalism career in Montana, working in Missoula, Anaconda, Butte and Billings. "The Big Sky, By and By," a collection of some of his newspaper stories and columns, plus a few essays and one short story, was published in 2011.