Harmon’s Histories: Remembering the 1895 explosion that brought Butte to its knees

J.R. Dutton of Butte was riding on a street car approaching the Garrison house when he noticed a fire in the nearby warehouse district. He saw James Steinborn, a local cop, turning in the alarm at Box 72 at Iron Street and Utah Avenue. He decided to hop off the car to take a look.

It was 9:55 p.m. on the evening of Jan. 15, 1895.

Dutton and a handful of other onlookers were soon joined by a couple hundred Mining City residents watching as local firemen arrived to fight the blaze that seemed to be centered at the Butte Hardware Company and Kenyon-Connell commercial facility.

Dutton heard someone shout, "There's powder in the building," but he said that was denied, and the firemen continued to attack the fire.

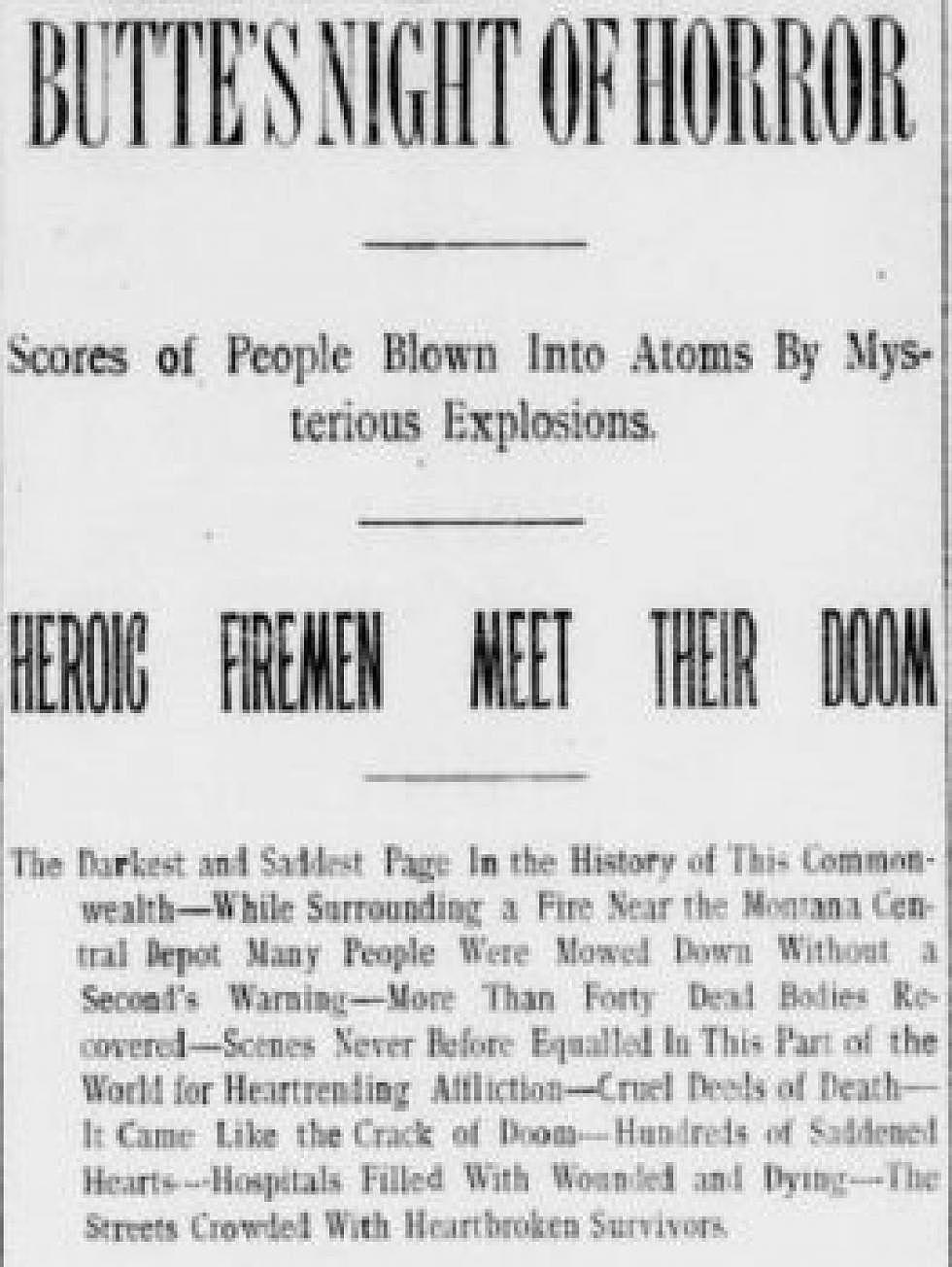

What happened next was described as the "most terrible calamity in the history of Montana."

At 10:08 p.m., "a deafening explosion occurred ... which shook the city of Butte to its foundation."

The Anaconda Standard reported a hook and ladder truck and its two attendants "were blown 50 feet into the air and torn into fragments." Only two of the first-responders and one fire horse survived.

Dutton said, "The sight was simply awful. The firemen were thrown in all directions, and the air was filled with shrieks and screams which could be heard even in the terrible roar."

Bystanders rushed in to help, when a second blast occurred. Dutton said, "I was knocked down and was senseless for several minutes." He was lucky – suffering only a broken arm and managing to walk to a hospital, where he was treated and interviewed by reporters.

Dozens of others were killed, hundreds injured. The official toll was placed at 58 dead, but it may have been higher, given the destruction at the scene. As the graphic newspapers of the day reported, only "a capful of blood ... (was) left of brave (Fire) Chief Cameron."

As snow covered the blast site the next day, the public and the press demanded justice. "Who was the man, or who the men, who violated the law by storing these deadly explosives in the city limits?"

The investigation centered on the Kenyon-Connell warehouse and the neighboring Butte Hardware warehouse. Owners of both businesses denied having anything but a small supply of explosives – W. R. Kenyon saying no more than a few boxes, only enough to fill orders in the morning.

Similarly, the Great Northern Railroad denied having any powder cars in the area.

In the midst of the pain and grief, the Anaconda Standard newspaper beat its chest, proclaiming itself "Montana's greatest daily," after it sold out its first edition and extras – leaving others to "read the Miner with its ... meager account," which it claimed had been lifted, in large part, from the Standard.

A coroner's jury convened in mid-January, and by the end of the month found Kenyon-Connell and Butte Hardware "criminally negligent and careless" for storing dynamite "far in excess of the amount allowed by law." They concluded the two companies were responsible for the deaths.

But a grand jury, meeting a few months later, said there was insufficient evidence to pin it on any individual(s) and were advised by the county attorney that both businesses were corporations – and corporations "cannot be dealt with criminally by this grand jury."

The Neihart Herald newspaper was shocked, calling the decision "a sore disappointment ... (given) the frank and honest statements of the coroner's jury upon the same case."

But civil cases did proceed – the first just before Christmas 1895, in which Mrs. Sophia Goddard sued for damages in the death of her husband. Albert Goddard.

Lawyers for Kenyon-Connell tried everything – from denying the explosion originated in their warehouse to "alleging that Goddard had no business on the grounds and that he was a trespasser there and assumed all risks and that, therefore, the company could not be held liable for damages."

The jury would have none of it, awarding Goddard $5,000 for the death of her husband.

Despite the setback, the corporations continued to argue in a series of subsequent civil cases that their officers had no personal knowledge of explosives being stored in the warehouse; that (even if they did) a city ordinance allowed it; and their corporate officers could not be held personally liable.

Finally, four years later – in 1899, the Montana Supreme Court, in a harshly-worded opinion, dismissed every one of those arguments, saying the very purpose of the company was to sell explosives, so it was impossible to believe the officers didn't know dynamite was stored in the warehouse.

Declaring the practice a "menace," the justices said it was "very hard to conceive of anything more terrible in its danger to life and property than a quantity of highly explosive powder kept near to where people live or do business."

If you'd like to learn more about the "most terrible calamity in the history of Montana," you can click on the following link. It'll take you to Gus Chambers' Montana PBS documentary from a few years ago, titled "HIDDEN FIRE: THE GREAT BUTTE EXPLOSION."

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula broacaster who writes a weekly column for Missoula Current.