Harmon’s Histories: A look back at Missoula’s last 100-year flood

We live in a wonderful place, a place where, as Norman Maclean wrote: “Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it.”

But as Missoulians place sandbags around their homes and the county commissioners sign an emergency proclamation, we’re reminded of the risks of being a “river city” when too many things merge into one.

In June of 1887, the Buckhouse Bridge over the Bitterroot River was washed out – “gone like a beautiful dream,” in the words of one newspaper reporter.

There were rumors “on the streets that the Blackfoot dam was in imminent danger of breaking, in which case the water of the Missoula River at this point would be swelled to an unprecedented extent, our bridge taken away, and communication with the southern portion of the county cut off.”

Trees, saw logs and other debris lodged against the Higgins Bridge. Men with axes, hooks and ropes worked to clear the jam as crowds gathered on the bridge to watch. Even as the bridge “trembled very perceptibly and they realized their danger ... the excitement acted as a charm with women and children as well as with men.”

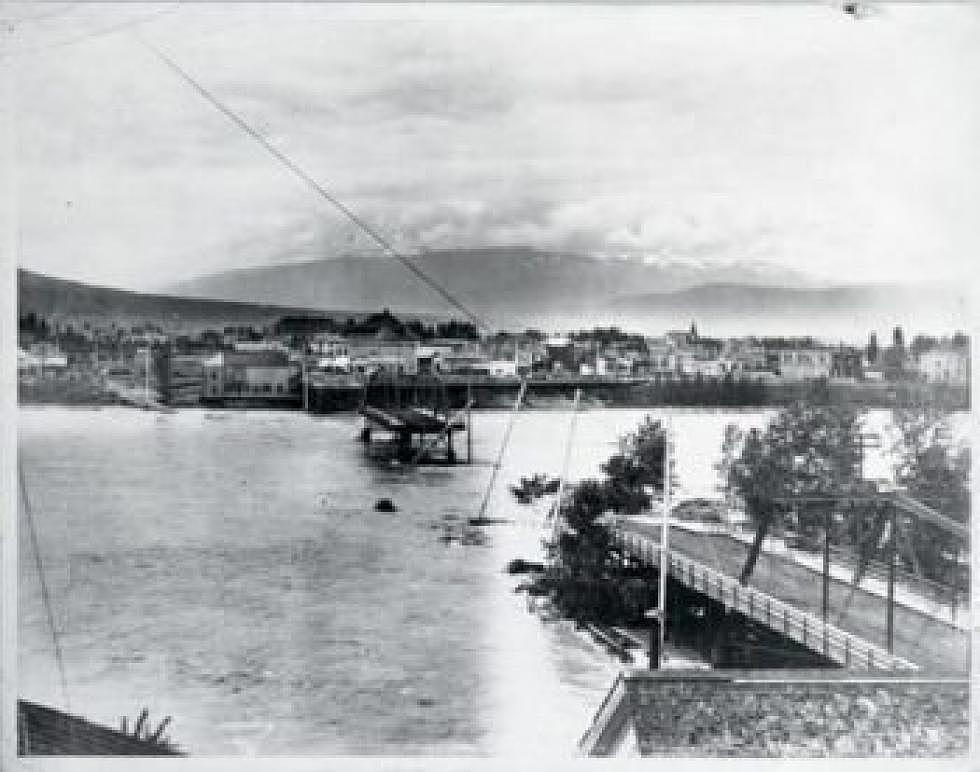

Again in 1894, the bridge was threatened by the force of the spring runoff. The island in the center of the river was underwater and the electric light works, located there, had to be shut down when the engine room was flooded.

But the granddaddy of all Missoula floods was in 1908 – dubbed the city’s “worst natural disaster.”

A visitor from Salt Lake City, stranded in Missoula for two weeks, said: “It was a remarkable thing ... I saw station houses, section houses, platforms and dwellings” floating down the river.

The north side of the Higgins Avenue Bridge collapsed on June 5. The south span washed out two days later, taking the phone lines with it.

A local newspaper reporter described the city as “divided, without bridges or communication from one side (of the river) to the other, (with) homes and property washed away.”

The power plant was so badly damaged, the only way to turn out the newspaper was to “install a gas engine to operate the typesetting machines and the press.”

Rattlesnake Creek, “ordinarily a mountain brook,” threatened to wash out the Cedar Street (now Broadway) Bridge. The bridge held for a while until, upstream, the rushing waters washed out the footings of the Higgins home, sending it down the creek, slamming “into the Cedar Street Bridge, carrying the structure downstream.”

But Missoulians proved resourceful. Within hours of the bridges washing out, a temporary footbridge was erected across the river and, within days, a temporary fire station was built on the south side.

An “army of men” was assembled to begin railroad repairs which would ultimately cost a $1 million (1908).

The Wenatchee Daily World called it “the largest single loss to which the railroad has ever been put by a natural catastrophe.”

An estimated 2,000 workers were needed to repair damaged tracks and washed-out bridges scattered along more than 170 miles.

In the weeks and months following the flood, a new steel bridge replaced the old “rattle-trap” Higgins crossing and a beautiful new train station was built on the site where the old “Puget Sound” depot had stood before it washed away.

Three years later, a Missoulian newspaper reporter reflected, “Think how the city itself has grown in population, in public buildings,” adding that it would be impossible to fully “tell of this growth and to enumerate the many things that date back to the disastrous flood week in June 1908.”

It’s wonderful being a river city, except when too many things merge into one.

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula news broadcaster, now retired, who writes a weekly history column for Missoula Current. You can contact Jim at harmonshistories@gmail.com.