Mary Moe: Birmingham’s children awakened America to the South’s racial terrorism

Last month, in a nod to Martin Luther King Day, I wrote a Missoula Current column about Dr. King’s remarkable “Letter from Birmingham Jail." As we celebrate Black History Month, here’s the rest of the story, the second in a trilogy.

Fifty-six years ago, if you were looking for the heart of darkness that was racism in America, you’d stop searching in Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham was the most segregated city in the United States. Its city code stipulated expectations for separateness in jarring detail, but it was its unwritten code that licensed racial terrorism.

When Nat King Cole performed there at the height of his popularity, Ku Klux Klansmen rushed the stage to attack him. One night, Klansmen grabbed a young black man out walking with his girlfriend and, after toying with him for a while, forced him to choose between death and castration. They performed the latter and then poured turpentine on his bleeding wound. Random bombing of black people’s homes was so common that the city's not-at-all-funny nickname was “Bombingham.”

Pumping blood into this heart of darkness was the woefully mistitled Commissioner of Public Safety, Bull Connors. An avowed segregationist, after the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision requiring school integration, Bull predicted “blood would run in the streets.” Under his jurisdiction, it did.

When the Freedom Riders passed through Alabama in 1961, Klansmen firebombed one bus and commandeered the other, “escorting” it to Birmingham, where some 60 additional Klansmen waited. Connor promised them 15 minutes to do whatever they wanted before he sent in police. Klansmen beat the riders emerging from the bus with pipes, wooden slats and key rings, some so severely they were hospitalized.

A heart of darkness, then. And as it happened, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was looking for just such a place to bring national attention to the brutal realities of racism in this country. The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth – who stayed in Birmingham after being beaten, after having his house bombed, after white businessmen told him pointedly, “If I were you, I’d get out of here” – urged King to come to Birmingham. All the ingredients were right for a confrontation that would finally open the nation's eyes to the ugliness that segregation spawned.

So King and the other SCLC leaders came to Birmingham. Every night, they fired up Birmingham’s black population in a local church, but in the morning too few were willing to do what needed to be done: Go to jail. They needed to fill the jails to get under Bull Connors’ skin, and it wasn’t happening. Some black businessmen refused any involvement at all, preferring to work with the white establishment for a better day, even though that better day showed no signs of dawning.

Days passed. Momentum ebbed. On Good Friday, King, Shuttlesworth and Ralph Abernathy made the decision to break the law and go to jail themselves.

I wrote last month about the remarkable letter that Dr. King wrote from that jai. As an English teacher, I’d like to report that King’s masterpiece of argumentation was the eye-opener that made the breakthrough that was Birmingham. But it wasn’t. Very few people even read the letter until the protest was long over. The breakthrough was the Children’s Crusade.

Even after King was released, black working people didn't show up in the numbers needed to fill the jails. You can understand why. This was Bombingham. If they missed work, they’d lose their jobs. If they went to jail, who would know or care what happened there? When King and his team and the news crews moved on, they would still live in a city that castrated young men on a whim, that bombed homes at night at will.

One of the younger members of King’s team, James Bevel, had an idea: Let’s make schoolchildren our foot soldiers. They don’t have jobs to lose. There are lots of them. Let’s fill the jails with kids. King was opposed to the idea initially, as I would have been. But Bevel persisted, and the kids insisted, and when King went off to a speaking engagement elsewhere, the children were deployed.

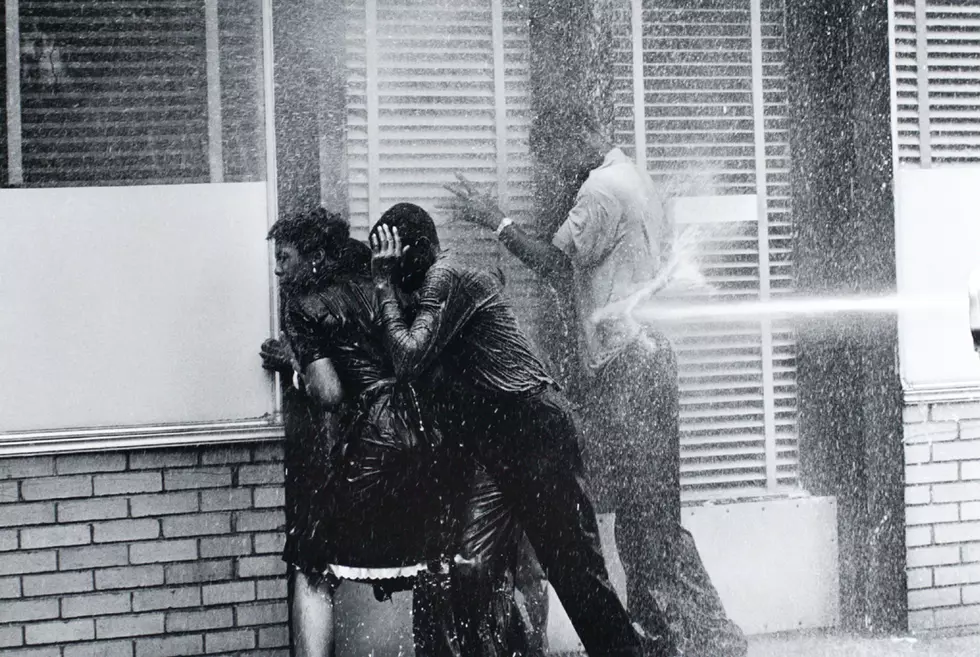

The rest is history. The kids came out in droves. The jails filled to overflowing, and still the kids kept coming. Bull Connors finally did what they hoped and prayed he would: He got tough. He called out the dogs and pulled out the firehoses.

On that day, a black businessman named A. C. Gaston was on the phone with a white lawyer, commiserating about the trouble King was stirring up in their town. As Gaston looked out the window, he saw the spray of a firehose send a group of children flying down the street like leaves.

“I can’t talk to you now – or ever!” he exclaimed. “My people are out there fighting for their lives and my freedom. I have to go help them.”

Soon enough, what Gaston saw, the entire nation saw: Images of children pressed up against buildings, enduring the lash of a water stream that could strip the bark off trees. Police dogs lunging, their teeth bared, at children. Open brutality on the streets of Birmingham, Alabama.

That’s what it took. The nation gasped. The Kennedy brothers got off the sidelines. The white businessmen in Birmingham began negotiating in earnest. By May, they had promised to take down the signs and discontinue other practices that enforced segregation there. In June, President Kennedy addressed the nation, saying:

The heart of the question is … whether we are going to treat [all] our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place?

President Kennedy didn’t live to sign the Civil Rights Act he proposed that night. Had he lived, he would have had a hard time getting it passed. But with a grieving nation ready to canonize him, with a Southern president succeeding him who knew a thing or two about cajoling Southern Democrats, the Civil Rights Act passed. It became law on July 2,1964, just one year and two months after schoolchildren became foot soldiers in Birmingham, Alabama.

It took frightful images, not reasoned words, to turn the corner in Birmingham. I wonder now whether that set a dangerous precedent. We read about the immigration crisis in the Mideast for years, but it took the 2015 photo of a Syrian toddler on a Turkish coast to poke us in the conscience. We’ve pretty much forgotten that plight now. We read about the changes in immigration practices at the border throughout 2017, but it took the image of a 2-year-old girl shrieking as she was being separated from her mother for us to object.

I’m glad we can still be reached that way, when images touch us viscerally. Words, especially the printed word, require thought, reflection, analysis – and the world of the printed word is disappearing. Replacing it is a world flooded with images every minute … too many to digest, so many we are increasingly too numb to disaster for even a visceral reaction.

Dr. King wrote something from his jail cell that haunts me still. He described his travels across the Southland and marveled at the South’s beautiful churches everywhere “with their lofty spires pointed heavenward.” Looking at them, he could not help asking himself, “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?”

One might ask the same question today as 3.1 million human beings no less God’s children than you or I seek asylum worldwide. They face a crisis of survival and present us with a crisis of conscience. Segregation in this country has ended, but the cognitive dissonance that keeps us from seeing what is in plain sight never really goes away … especially when we are continually beckoned back into the heart of darkness with emotion-laden exaggerations and fear-mongering stereotypes. The horror. The horror.

Mary Sheehy Moe retired from the Montana University System in 2010 and has since served on the Great Falls School Board and in the Montana Senate. She lives in Great Falls, where she is now a city commissioner.

https://missoulacurrent.com/opinion/2019/01/martin-luther-king/