In Missoula, governor’s council on climate solutions struggles to find middle ground

Finding ways to combat climate change that most of the state can accept is a daunting task, but it’s one that about two dozen Montanans need to complete before June.

On Monday, the Montana Climate Solutions Council met at the University of Montana in Missoula to develop a first draft of a report outlining recommendations of what the state could do to either adapt to or mitigate climate change. The council hoped to have initial recommendations by the end of the month, so they could put it out for public comment.

The final recommendations are due to the governor by June.

But as with Gov. Steve Bullock’s other councils on grizzly bears and forest management, they were still struggling at the halfway point with many of the topics and how they would interact.

On Monday, they considered how various sectors, like agriculture, could adapt to or endure climate change, and later they would consider what could be done to mitigate the effects and what innovations to prioritize.

“I’m not worried about the chaos we’re in,” said John Tubbs, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation executive director. “We will produce a good quality report for the governor. And it is going to need to be narrower in focus. But it also is going to task us to continue this conversation and take action.”

Subgroups of the committee had done their homework and had written and digested several whitepapers on everything from water to wildfire. But because the council members come from different backgrounds, that seemed to add more complexity and questions to each topic area.

The council agreed to most of the recommendations each subgroup put forward except during the discussion of wildfire and forest health adaptation. Under a recommendation to “increase forest products for carbon storage,” some members objected to a proposal to develop energy markets for biomass.

Biomass includes the bark and small trees and branches that loggers collect in slash piles. These can be burned where they’re piled but some burn them in biomass incinerators for energy.

The problem is that burning biomass releases carbon, and biomass burners are often less efficient than coal or natural gas plants. So it does nothing to stop climate change.

Tubbs withdrew the proposal.

“It’s not necessarily a climate issue,” Tubbs said. “It’s worded in such a way that, for this particular day, let’s exclude that bullet point. We can work on it more if it comes back in. But I recognize the conflict between the greenhouse gas committee and others.”

One tool that played into topics of agriculture, forestry and rangelands is a carbon-credit market. That would provide economic incentive to conserve trees and grasslands that store carbon, although it doesn’t provide much to individual producers.

UM Forestry professor Solomon Dabrowski said the Lubrecht Experimental Forest is already dabbling in carbon credits, although it was difficult to get the process going and it requires long-term commitment to quantifying the carbon and getting third-party verification. Universities have the wherewithal to do that but maybe not smaller landowners.

The biggest catch right now is that only one state – California – has a cap-and-trade system that would pay carbon credits, although New Mexico and Nevada are exploring the possibility. But Dabrowski said the best way to set up carbon markets for optimal use is by region, rather than state-by-state.

Rangelands present a climate change quandary, because healthy rangelands can sequester carbon but cattle add methane to the atmosphere. Methane is worse than carbon as far as trapping radiation. Tubbs said it wasn’t worth considering.

“What we know about native rangelands is grazing has to occur. Exclusion of grazing will result in a loss of rangeland because trees grow on it,” Tubbs said. “I don’t know what the alternatives of methane-producing ungulates are but we’re going to have an ungulate out there eating the grass or we’re not going to end up with grass in the end.”

While incentives help prompt action, committee member Alan Olsen of the Montana Petroleum Association, said it would be better if incentives were voluntary, because stockgrowers weren’t likely to support mandated practices even if incentives were involved.

Compromise, while beneficial in other arenas, will obviously diminish the state’s response to climate change. For example, committee member Gary Wiens of the Montana Electric Cooperatives Association said electric coops and other organizations would probably take issue with a recommendation to conserve and restore species and habitats to preserve ecosystem functions.

“I would suggest language that would say, ‘With consideration of economic impacts and private property rights,’ and then the rest” Wiens said.

Patrick Holmes, Bullock’s Natural Resource Policy advisor, said all the recommendations would go through “heavy redrafting” by the end of the month.

“We’ll talk about who needs to be engaged and how later,” Holmes said. “If there aren’t significant issues to flag (now), the recommendations will proceed in the draft that will go out to the public, and you all will have an opportunity to review the sections and provide feedback.”

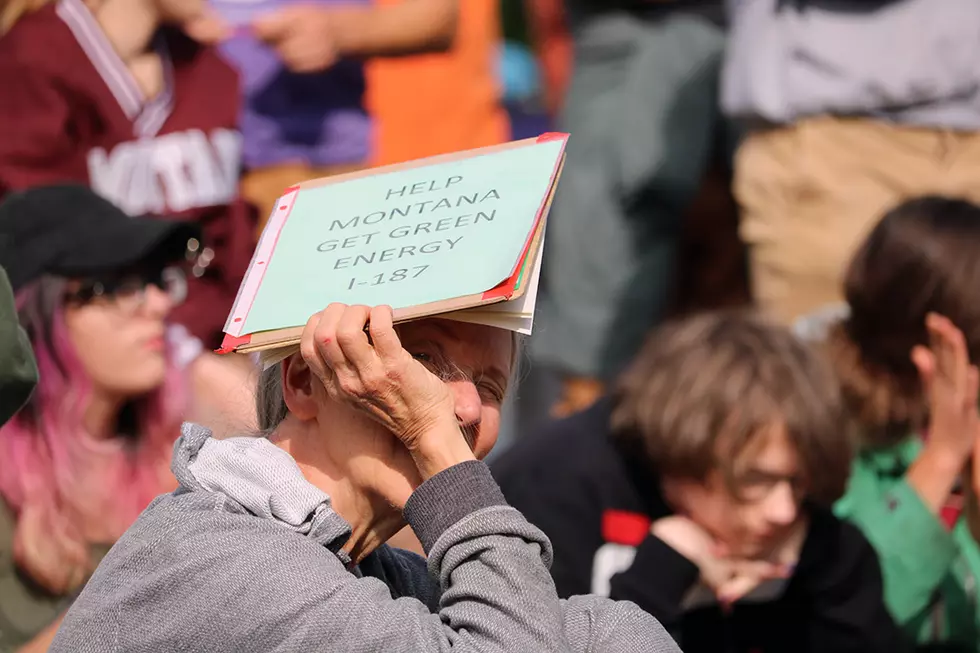

It was clear at the end of the day that some of the public weren’t impressed with the work the council was doing.

Four young adults stepped to the microphone to say that the council wasn’t recommending enough action to address the climate crisis. Eliot Thompson and Daniel Carlino said more needed to be done to reduce fossil fuel emissions, including putting a ban on fossil fuel infrastructure.

“Anything short of that will not only demonstrate a lack of commitment to safeguarding our water resources but it will also demonstrate the corrupting influence of the polluting fuel industry on this process,” Thompson said.

But even older Montanans had concerns. Kristen Walter of Bozeman said the council was making recommendations that didn’t provide ways to measure success. She suggested that fuel prices should reflect the carbon content so people understand how they add to climate change.

“How can we really make a difference and how can we do it quickly,” Walter said. “With emissions reductions, how do we do that on a massive scale as quickly as we can?”

Retired U.S. Forest Service forester Dave Atkins suggested that the council adopt a system of carbon fees and dividends rather than cap-and-trade because it returns money to the people.

“During the time frame of 1983 ‘til now, we’ve defined the problems really well. We’ve defined lots of solutions and this is the time to move on with action,” Atkins said.

The committee finished its deliberations on Tuesday.