Tribal leader: Without Election Day voting, ballot collection, Native Americans don’t have a voice

(Daily Montanan) Blackfeet Tribal attorney Dawn Gray described the relationship between the tribe and election officials in Glacier County as “hostile” and filled with retaliation.

Her description of the relationship with Pondera County was even worse: The tribe had to sue in 2020 just to get satellite voting in Heart Butte when the county refused.

“I have a job, income and a car. I can only imagine what it’s like for one of our residents who is homeless,” Gray said in court on Tuesday.

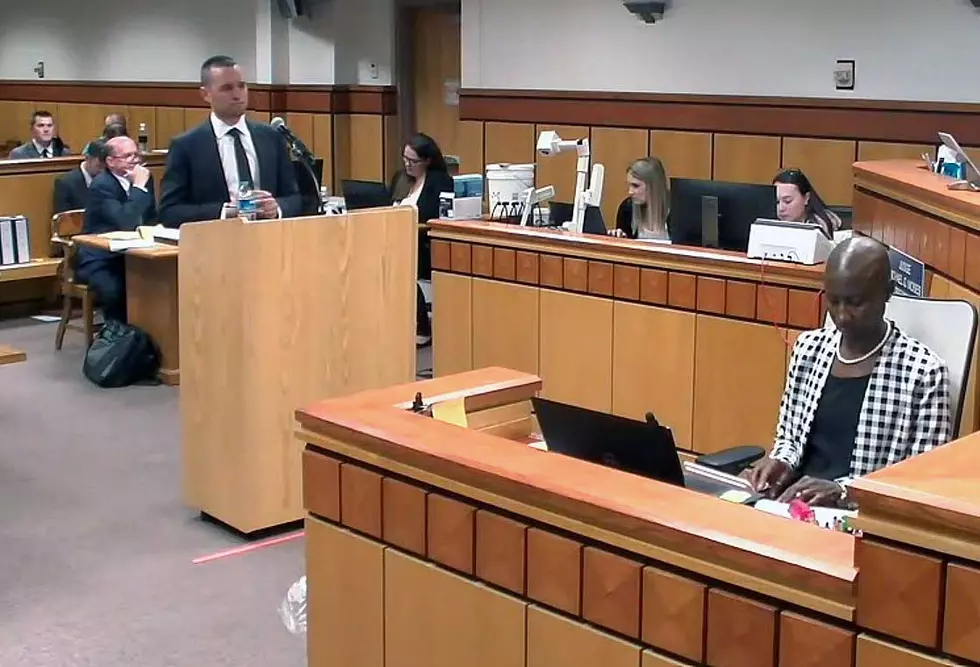

Tuesday was Day 2 of a two-week trial where three voting laws are being challenged as unconstitutional. Those three laws stopped Election Day registration, paid ballot collectors and changed the acceptable forms of identification needed in order to cast a ballot.

Testimony in Yellowstone County District Court on Tuesday ranged from expert analysis of the voting laws, while also focusing on those who were affected by the changes the 2021 Montana Legislature implemented in the name of election security and taking stress off rural counties.

However, a large group of plaintiffs, including the Blackfeet Nation, the American Civil Liberties Union and Western Native Voice, have all said the new laws violate state constitutional protections for voting, and unfairly discriminate against Native Americans living on reservations.

Shutting the door on Native American voices

In court testimony, Gray described the challenges of living on the reservation – from the lack of reliable transportation to the lack of internet coverage.

She was even more graphic when it came to describing the living conditions and poverty that exist on the 1.5 million acres that spans Glacier and Pondera counties.

“Many have broken windows and broken doors. We are on a floodplain, so many (homes) are filled with mold,” Gray said. “They would not be what is classified as a ‘livable standard.’”

The waiting list for tribal housing is more than 100 people, and 200 people want on it, but are not eligible because of failure to pay rent.

In Heart Butte, the tribe recently had to remove 12 kids from a house with no windows and no doors.

Because the U.S. Postal Service doesn’t have residential delivery, Gray said, tribal members are forced to use a system of post-office boxes where residents share a box, but lack a physical address. This presents a problem when it comes time to vote because they don’t have an address.

But in a place where the winds are so strong that they tip semi-trucks, sometimes, even the mail from Great Falls is delayed for days.

“Our culture, especially in tribal elections, is based on voting at the polling place, but if you don’t have your basic needs for the day, like transportation, you’re not going to the polling place. In some circumstances, it’s despair because you don’t have transportation and you don’t have a ride or gas money,” Gray said.

She told the court that in 2020, the tribe was forced to spend nearly $10,000 because Glacier County pulled ballot drop boxes three days before the election. She testified that the tribe decided to employ ballot collectors because of that incident. And she also reported that county officials had moved polling locations without adequate notice.

Gray also said that Western Native Voice, a grassroots group organized to help Native Americans participate in democratic processes, was one of the few groups that could help tribal members in places like East Glacier, St. Marys, and Heart Butte vote.

“Without them, they wouldn’t be able to vote,” Gray said.

Even without the tribal funding to pay ballot collectors, she said the Blackfeet Nation would still be unable to employ paid ballot collectors. She said the tribe has considered the possibility, but rejected it.

“If we interpret (House Bill 530), will we be subject to the fine? Or will the ballots be rejected?” Gray asked.

Language in HB530 said that ballot collectors must not receive any “pecuniary benefits” but the law exempts governmental officials. Gray said it’s clear that the lawmakers meant to exclude post office workers or elections officials, but she’s not so sure the new law would encompass tribal government, which is often referred to differently in other parts of state law.

“If you take away Election Day registration and ballot collection, you shut the door on our voice,” Gray said.

No ballot for you

Thomas Bogle of Bozeman testified that he registered to vote after he and his wife moved from Colorado to Montana. Both he and his wife completed paperwork at the DMV in Bozeman for absentee ballots as they got Montana driver’s licenses. She got her ballot in the mail. He did not.

But before Election Day, he checked his voting status, finding out that he was still listed as a Colorado voter. He then filled out another form, but still did not receive a ballot. When he went to the Gallatin County Election Office in November 2021 to vote in a municipal election, he was told by a clerk that the paperwork from the DMV was still in process, but because of the changes to the law, he would not be able to vote that day.

“I was wrongly denied the opportunity to vote, and this is a chance to correct that,” Bogle said in court Tuesday, responding to why he was appearing. “(The clerk) made mention of the same-day voter law and he explained that the Legislature had passed it and because of that law, I was not going to vote.”

Expert testimony

The day opened with Professor Ryan Weichelt of the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire defending a study that he completed that calculated driving times and distances to post offices, county seats and Department of Motor Vehicle locations – all places where registering or voting activities happened.

Attorneys for Secretary of State Christi Jacobsen, who is called upon to defend the new laws, pointed out that 17 places Weichelt had excluded from his study likely skewed the results, tilting them toward longer driving times. When Weichelt was called upon to defend the locations he excluded, he said they were because of unique natural obstacles, like winding mountain roads, which made them unlike other locations.

However, attorneys brought up several maps that showed fairly routine and sometimes straight roads without obstacles, like the route from Springdale to Big Timber along Interstate 90.

Attorneys also pointed out that Weichelt had not weighted his study to look at how many residents were affected by long travel times to those locations, and he had failed to consider whether many or a few were burdened by some of the longest travel times.

The group of plaintiffs also relied upon Carroll College Professor of Political Science Alex Street, who focused much of his nearly day-long testimony on Election Day voting patterns, sometimes called “same-day voting.”

House Bill 176, passed by the 2021 Legislature, changed Election Day voting, pushing it back to the day before election at noon. Lawmakers said the change was necessary to give smaller rural offices more time to prepare for the election.

“Attention to elections tends to peak on Election Day,” Street said. “That’s because coverage in the media and advertising buys and the conversation peak then.”

Montana adopted Election Day registration in 2005 and Montana voters have repeatedly supported the measure.

Street’s research revealed that half of all voting done during the “late registration period” – that is, 30 days before the election – is normally done on Election Day itself, while the other remaining half is spread out during those other 29 days.

“Voting and registration are less costly and potentially have benefits, especially with a highly mobile population,” Street said.

And Gray, of the Blackfeet Tribe, argued that with chronic homelessness in places like the Blackfeet Nation, tribal members often have to move from place to place, often “couch surfing,” which makes having a stable, permanent address difficult.

Street’s testimony also supported the idea of paid ballot collectors as a means of overcoming some of the obstacles found on Montana’s reservations – for example, lack of mail service.

Gray testified that the U.S. Postal Service doesn’t have enough post office boxes for the nearly 6,300 adult enrolled Blackfeet tribal members, and it doesn’t deliver residential mail, meaning that many share post-office boxes. For many, Street said, ballot collectors are a vital link to getting the ballots to a collection site.

Street noted that Montana tribal members use Election Day registration at about double the rate as other residents who don’t live on the reservation.

“There is pretty clear and consistent patterns and high quality data that Native American in Montana are more reliant on Election Day registration than other people,” Street said. “There is a big body of research on EDR and it’s been fairly clear and the consensus is that it has a positive effect on voter turnout.”

That turnout, Street told the court, ranges from 1.5 to 3 percent.

“That emphasizes that Election Day is special,” Street said.

Voter fraud

When the 2021 Legislature passed a raft of laws changing the voting system in Montana, lawmakers in the majority argued they were concerned with voter fraud and election integrity. Street’s research addressed those issues, including research on Election Day and ballot collecting.

Street noted that most of the things outlawed in HB530, which governs paid ballot collection, like tampering with a ballot, changing a ballot or destroying a ballot are already illegal under Montana law.

“All suggestions of fraud … under (HB)530 are already illegal under Montana, and there’s reason to be skeptical about the claim that it will reduce fraud,” Street said.