While in disrepair, Fort Missoula hospital could see new life

Martin Kidston

(Missoula Current) Decades of neglect and water damage have taken a toll on the old hospital at Fort Missoula, where dead birds and pigeon waste litter the upper floors.

Chips of lead-based paint are peeling away, the windows broken. One floor has been used as a shooting range, the bullet holes evidence of target practice. The old basement boilers are rusted, and a frigid chill pervades the building.

But Missoula's Max Wolf, owner of North of the Boarder LLC, and David Gray of DVG Architecture have taken a liking to the place, as bad as it is. Wolf is ready to invest many millions of dollars to restore the facility to its former self, though doing so will rest in the hands of the city's decision makers, from the Historic Preservation Commission to the City Council.

“This building has been on Missoula's most endangered building list since 2008 because the roof was failing. It's never been fixed,” said Gray. “This is going to be really expensive. We're definitely in the millions of dollars.”

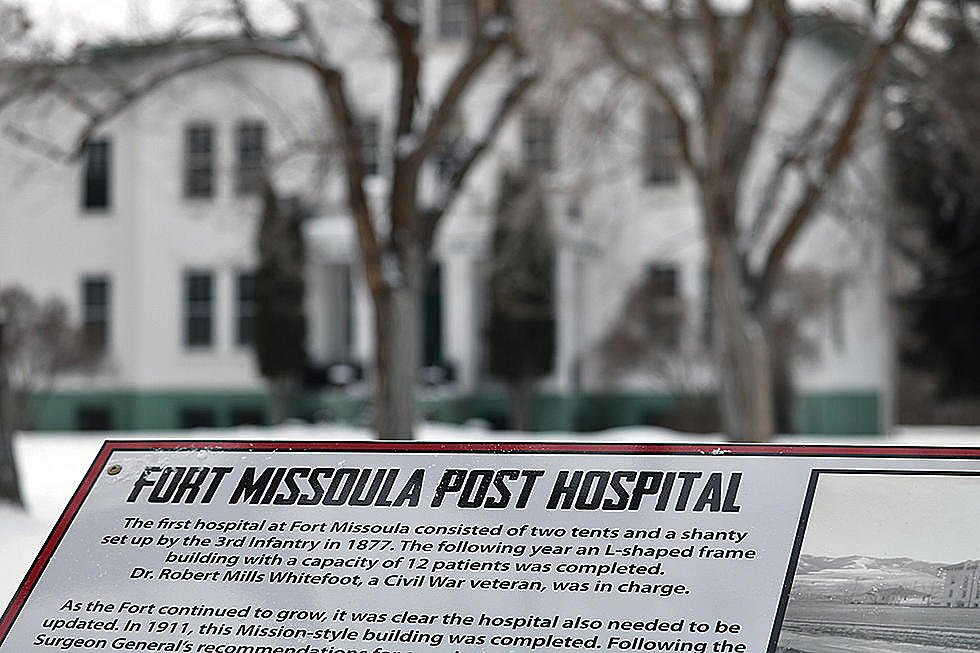

The hospital was built in 1911 to treat members of the U.S. Army, followed by those held in the detention camp during World War II. Gray said the military decommissioned the building in the 1940s and it sat vacant for the next 20 years.

In the 1960s, the building was purchased by a private owner who tried unsuccessfully to restore it. It sat vacant again in following years and fell deeper into disrepair.

But Wolf purchased the building and surrounding five acres in 2019 and has plans to restore the facility. The University of Montana graduate specializes in historic renovation, as does Gray, who helped restore the Radio Central Building downtown to its 1890s grandeur.

“Seeing what's happened to historic buildings throughout Missoula, we bought this in 2019 with the intention of restoring this hospital building back to its potential,” said Wolf. “We've learned a lot about the history since purchasing the property. It's a big part of how we've approached the design and plans for the property.”

Plans for Restoration and Development

Giving the building's historic significant and the steep cost of saving it from eventual collapse or removal, Wolf has proposed a small development on five acres of private property adjacent to the facility.

The proposal would include a small retail space to house a restaurant or cafe. He believes that would cater to the hundreds of workers at Fort Missoula, along with those who utilize the nearby regional park and athletic fields.

Roughly 15 residential units would be tucked quietly behind the hospital on the property, with 25% of them reserved as workforce housing, Wolf said. The revenue generated by the development would help fund the hospital's restoration.

“When this was purchased in the 1960s, they tried to restore it and save it, and that got stopped. My client is the second developer who has bought this and will try to save it,” said Gray. “It won't get more times to be saved. It's a good opportunity for this building to get refurbished.”

Gray said the development would respect the fort's history and architecture. It would preserve open space, protect the viewshed, offer a plaza for special events, and include sidewalks that tie into a trail system proposed by the city's parks department.

“Fort Missoula didn't develop all at once,” said Gray. “We've specifically not made everything look like the Mission style so to not confuse people over what's new and what's old. There's no false history. But the buildings will be very historically sensitive styles of architecture.”

Restoration Funding

Hints of the hospital's past are still evident despite the mishmash of changes that have taken place over more than a century. They uncovered high, coved ceilings after taking down false coverings. Cast iron pipes still feed bulky radiators, though the coal room in the basement sits empty and the massive boilers cold and idle.

White-tiled hospital wards, century-old bathroom fixtures and a strange room with a cast-iron prison door let one's mind imagine the facility's early days, back before the nation entered its second world war. In one basement room, an old rocker sits empty and eerily faces a pallid, peeling wall as if poised for punishment.

Gray grins, saying the building is considered the eighth most haunted place in Montana. But if approval is granted, the facility would again team with life, the empty hospital rooms used not for surgery but as offices.

“This is a private development with the intention of being a community space,” said Gray. “The zoning out here is limited in what it allows. But that doesn't sustain the fort, and that's been the real problem.”

The building currently faces a future similar to the downtown mercantile, which fell into such disrepair that it became cost prohibitive to restore it. To the chagrin of some, it was eventually razed to make way for new development.

Wolf and Gray hope to avoid that but need approval to include the small accompanying development to fund the work. Restoration will need seismic retrofitting, window replacement, new electrical, plumbing and mechanical systems, wall repair, roof repair, and bringing the building up to modern codes.

“There's so much damage in the roof, I wouldn't be surprised if we had to take it off and rebuild it,” Gray said. “We're talking a lot of work, not to mention the water damage. It's going to be expensive, and it will require funding, which is what the small development will provide.”