Harmon’s Histories: Hitch a ride back in time on the Lamson Cash Railway

Jim Harmon

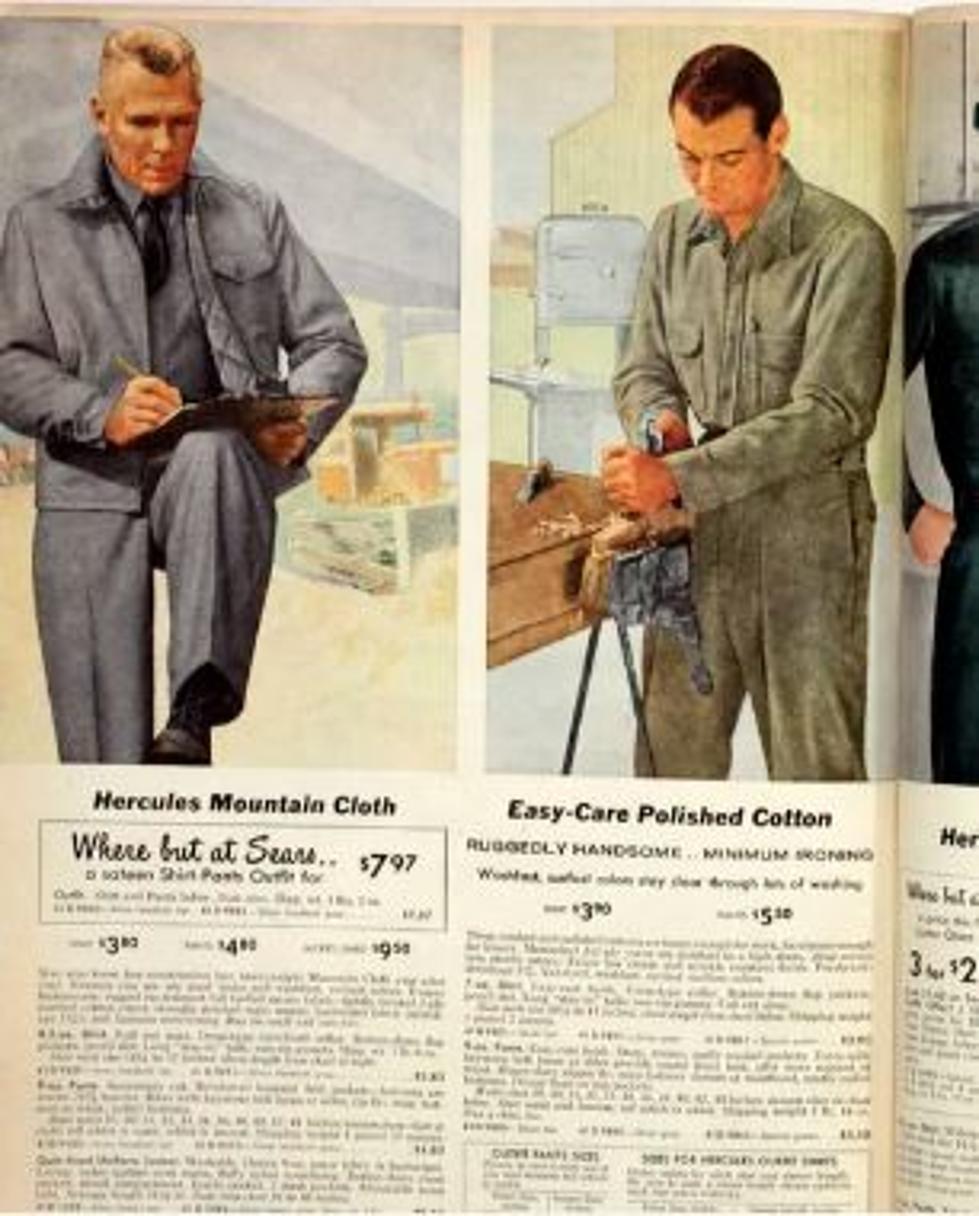

If you grew up in a small town in Montana in the 1940s and '50s as I did, you know shopping for clothing was a challenge. As a result, our family relied largely on Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward's mail-order catalogs.

Should we need something more quickly, or just wanted to make sure it would fit without going through the lengthy process of returning and reordering, we did have a couple of options.

For “fancy clothes” like men’s suits and such, there was Don’s Men’s Store (run by a neighbor of ours). For specialty items (like a high school letter sweater), we would go to the local sporting goods store.

But for everyday wear (T-shirts, underwear and blue jeans), we would go to the local J.C. Penney store, where they used a fascinating system to handle cash and file receipts.

Here’s how I recall it from my childhood memories: The clerk on the main floor would take the customer’s payment in cash or check. He would then place the money, along with the clerk’s receipt, into a container not all that dissimilar from a fruit canning jar.

The jar was then screwed into to an overhead lid hanging from some wires, following which the clerk would do his best impression of Johnny Unitas attempting the greatest pass of his career, sending the jar flying up the wires to the cashier’s office in the loft above.

As a child I had no idea, or any interest, in what the system was called. So recently I looked it up. It’s called the Lamson Cash Railway. The system was invented by William S. Lamson of Lowell, Massachusetts in 1878. He patented the system in 1881.

Drawings of the devices, however, contradicted my childhood memory of the “Johnny Unitas pass.” There was apparently a spring-loaded lever used by the clerk that moved the container up the wires. I hate when reality challenges my memories!

But I did discover some fun facts along the way. Apparently a few employees at various stores using the pulley system would send spiders or mice (both dead or alive!) inside the canisters to squeamish co-workers. Others would send gossip or romantic messages.

Anyway, I found that one of the best online sources for information about both Lamson and J.C. Penney is the Waltham Museum, built in the 1970s to “preserve and reveal the remarkable hidden history of Waltham, Massachusetts.”

The Waltham company, of course, was primarily a maker of watches and clocks. Many of the company’s historic timekeeping items are on display.

But the museum is also a treasure trove of information about the Lamson Cash Railway, J.C. Penney and his company.

James Cash Penney Jr. was born in Missouri in 1875. His father, it is said, told the boy that when he turned age 8, he’d have to start buying his own clothes.

J.C. wanted to be a lawyer, but when his father died, he had no choice but to go to work to support the family. He took a job as a store clerk, and the rest is history.

By the early 1900s, Penney so impressed one store owner that the merchant gave him part ownership of the business, which J.C. parlayed into franchises nationwide.

Penney was apparently what we now term a workaholic. He was said to have worked “five days a week in his New York office until his death at age 95 in 1971.”

Oh, by the way, in 1949 the Lamson company acquired something called the pneumatic tube system. The earliest of these systems involved a gasoline engine powering a large fan to create compressed air. Valves would be turned on or off to send containers flying hither and yon.

Such systems are still used today at your local drive-through bank, although I suspect there’s no gasoline engine in the bank basement.

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula news broadcaster, now retired, who writes a weekly history column for Missoula Current. You can contact Jim at fuzzyfossil187@gmail.com. His best-selling book, “The Sneakin’est Man That Ever Was,” a collection of 46 vignettes of Western Montana history, is available at harmonshistories.com.