Harmon’s Histories: Martin Bray killed ex-wife, innocent bystander in jealous rage

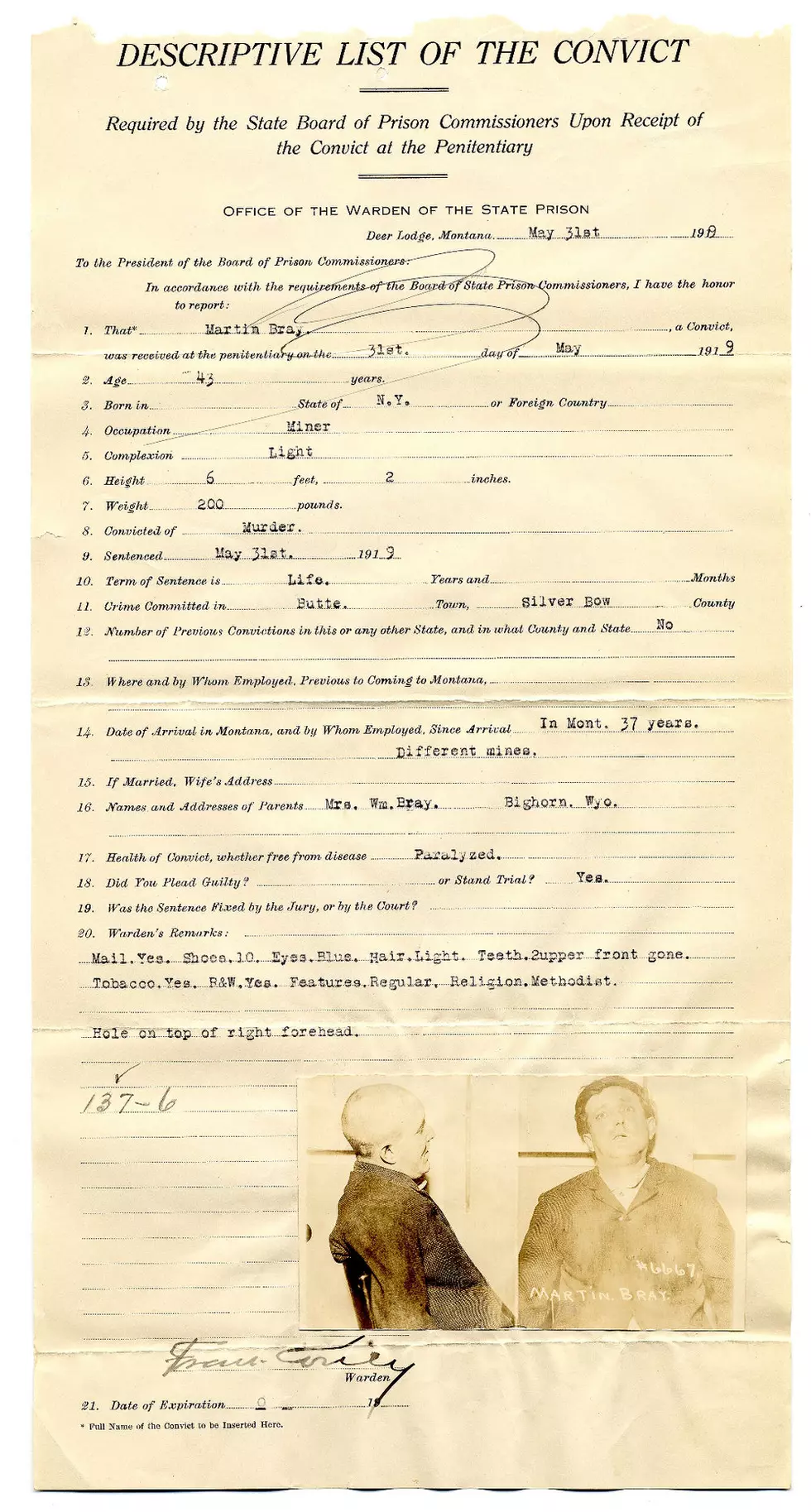

On the Montana State Prison intake form, the Warden described Inmate No. 6667 as a male, 6-foot-2, 200 pounds, shoe size 10, with blue eyes and a few missing front teeth. On a separate line was a curious note: “hole on top of right forehead.”

Forty-three-year-old Martin Bray was a New York native who had moved to Butte in 1917. On May 31, 1919, he began a life sentence for murder.

Bray had shot and killed his ex-wife, Gladys (Daisy) Alston Bray, and her male companion the year before, as they stood on a busy street corner in Butte.

Witnessing it all were Gladys’s three children (from a previous marriage) and hundreds of theater-goers. They then all watched as Bray turned the gun on himself – resulting in the bullet “hole on top of right forehead.”

From his hospital bed the day after the shooting he told police, “My wife’s acts drove me to it.” He claimed to have been in a “jealous rage” over his ex-wife’s alleged infidelity. When he saw her with a companion on the street corner, he just “opened fire.”

That was bad enough. But he also had shot the wrong man.

Her companion that day, May 16, 1918, was not the man who “had broken up his home,” but a complete stranger. According to press reports, the male victim, K. S. Showers, was a mechanic who repaired “phonographs, sewing machines and similar instruments.”

So who was Martin Bray, this assailant who admitted he was in a “jealous rage?”

At the time of the shooting, Bray was working at the Speculator mine in Butte. Interestingly, some years earlier Bray had actually served as a deputy sheriff in Helena, where he’d been wounded in the line of duty. He still carried a bullet in one leg and had a “scar on his breast.”

While there was no question that Bray had murdered K. S. Showers and “Daisy” Bray (he admitted it), there was a considerable question about whether he was sane at the time.

At his 1919 trial, “two physicians testified that the defendant was insane and two declared him to be sane,” reported the Great Falls Tribune.

An expert in bacteriology then told the court that he had studied some of the spinal fluid collected during Bray’s surgery. He claimed the test “showed Bray (was) deranged.”

Bray’s first ex-wife, Mrs. Julia Haas, certainly made clear in her testimony what she thought of the defendant.

“You would not say a word to keep your former husband from hanging, would you,” asked the defense. “I certainly would not,” responded Mrs. Haas.

Bray’s attorney, Wellington Rankin, made a “powerful argument for the defense.”

The Butte Daily Bulletin reported, “Rankin is strong on the emotional stuff. If any of those jurymen were shy on conscience to start with, they must have felt one sprouting before Wellington got through. The man is sincere, too. Whether or not Bray is shamming, his attorney is not.”

The jury only took only three hours to find Bray guilty, sentencing him to life in prison.

In late 1920, Bray went back to court to ask for a new trial. The request was denied, but “through some legal entanglements,” he managed to stay in the Butte jail for a considerable time, rather than being returned to prison.

“Considerable time” might have been an understatement. Newspapers reported Bray was “growing fat and gaining renewed health and vigor as time goes on.”

They also claimed he had “feigned serious illness” so that he could be rolled about in a wheelchair, with “court attendants carrying him on a stretcher between the jail and the courtroom.

Backing up those claims, one news reporter asserted, “After he was placed in the state prison he was denied the wheelchair and given a pair of crutches (which) he soon discarded.” During his time back in the Butte jail, “he walks with a quicker step than some men many years his junior.”

Unfortunately, those are the last news articles to be found. The press appears to have lost interest in Bray after his appeal was denied. Not a single story can be found in the latter 1920s or decades following – not even an obituary for the man.

So we’re left to wonder. Did he serve out his term? Was he released? Or did he die in prison?

The impetus for this story came from old prison records which are now available through digital files created by the Montana State Historical Society’s “Montana Memory Project.” You can check out those files, here.

The rest of this story was gleaned from old newspaper stories, digitized here and elsewhere.

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula news broadcaster, now retired, who writes a weekly history column for Missoula Current. You can contact Jim at harmonshistories@gmail.com. His new book, “The Sneakin’est Man That Ever Was,” a collection of 46 vignettes of Western Montana history, is now available at harmonshistories.com.