Montana scientists issue climate warning after Trump pulls from Accord

One week after President Donald Trump shunned the world’s leading scientists and pulled the United States from the global pact on climate change, more than 1,200 U.S. business leaders, governors, mayors and college presidents signed an open letter to the world.

Despite the president’s decision, they wrote, America would continue to support climate action in hopes of meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, even “in the absence of leadership from Washington.”

If they succeed, the world’s big coming-together may still hold planetary warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius.

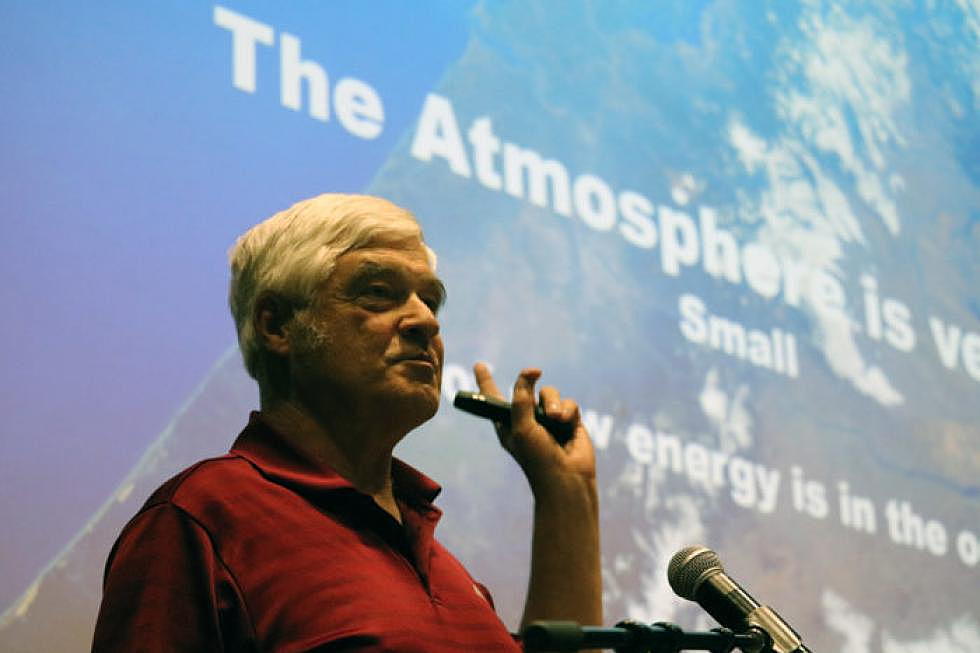

“I’ve never seen anything like this in my life,” said Steve Running, a Regents professor at the University of Montana and a global expert on ecosystem monitoring. “I’ve never seen, in one week flat, an open denunciation of a presidential declaration on any topic. It’s so unprecedented, I don’t think any of us know where this is going.”

Running, who shared in the 2007 Noble Peace Prize for his work on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, joined a team of experts at UM on Monday night to take a broad look at the science behind climate change and the impacts a warming climate will have on the state.

From the extinction of species to shifting ecosystems, the planet’s warming temperatures and changing weather patterns will alter Montana’s landscape and economy, with its climate more comparable to western Nebraska than the Northern Rockies.

The state’s forests could see widespread die-off as rainfall becomes scarce. An early snowmelt will leave streams depleted, the water warming as temperatures soar in the summer months.

The state’s prized fisheries will suffer and even the snowshoe hare may struggle, as it’s left with a white coat against a brown forest landscape. The number of days below freezing will drop, while the days with temperatures over 90 degrees will climb.

Invasive insects will thrive and proliferate.

“In Montana, the projections of business as usual take us up on the order of a 12- to 14-degree temperature increase by the end of the century if we continue with our fossil fuel-energy economy,” Running said. “All the policies and politics about climate change are about driving the emissions down to drive the temperature down.”

As of Monday, Montana had not joined the growing coalition of U.S. states committed to upholding the Paris Accord. While Gov. Steve Bullock criticized the nation’s pullout from the global climate pact, calling it “short-sighted and dangerous,” he is not listed as one of the governors to have joined the new coalition.

Still, a recent survey found that more than 83 percent of the state’s farmers currently see climate change as a problem. Other groups, ranging from the Montana Wildlife Federation to the Montana Farmers Union, have addressed the issue over the past week, citing impacts to the state’s economy if global temperatures aren’t held in check.

In Missoula, hundreds have marched through the downtown streets calling on the state’s congressional delegation to take a stand.

“The majority of Americans and Montana believe global warming is happening and support action to reduce emissions – they even trust scientists,” said Nicky Phear, director of the Climate Change Studies Program at UM. “But the public is still confused whether humans are the primary driver of that change, and they’re unsure if there’s scientific consensus.”

While climate experts say that scientific consensus is firm, climate-change deniers, including the president, have muddied the waters. Trump famously called climate change “a hoax” perpetrated by the Chinese during his run for president, and he has yet to answer direct questions regarding his stance on the issue.

Despite the deniers, Running said scientists have known about increased levels of carbon dioxide and its effects on the atmosphere for more than a century. That understanding surfaced in 1896 when Svant Arrhenius first intuited the consequences of burning coal to heat London.

More recently, Montana resident and scientist David Keeling began modeling and measuring CO2 in the atmosphere in 1958, developing what’s become known as the Keeling Curve. The amount of CO2 locked in the atmosphere has increased every year since, Running said – the results replicated at stations across the planet.

The resulting radioactive forcing, or solar energy, has trapped an energy increase of 2.3 watts per square meter. Running admits it’s a difficult equation to comprehend, though he compared it to a single Christmas tree light placed on each square meter of the planet – across the entire planet.

“That’s the additional energy being trapped,” Running said. “That’s the greenhouse effect. And for this example, you have to use the old-fashioned tree lights, not the new LEDs.”

All those tree lights put out heat. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the average global temperature in 2016 was 1.69 degrees warmer than the 20th century average. That surpassed the previous record set in 2015 by 0.07 degrees.

Since the start of the 21st century, NOAA reported, the annual global temperature record has been broken five times, including the years 2005, 2010, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

As much as 95 percent of that heat has been absorbed by the ocean, Running said, leading to warmer waters and changing weather patterns. Sea levels are rising and storms are growing more violent while some parts of the planet aridify – a fact that may stand in Montana’s own future.

“This ramp-up started in around 1980,” he said. “We didn’t really see it until about 2000, when we looked backwards. If people think global warming is something new that’s just starting up, we have abundant evidence that it’s been going on on the order of 40 years already.”

While the global warming “theory” plays out in real life, Running said, evidence suggests it has finally caught the world’s attention, as evidenced by the Paris Accord and the “We Are Still In” letter penned by 1,200 leaders across the U.S.

The planet’s top fossil fuel emitters still include India, the European Union, the United States and China. But emissions in the U.S. peaked around six years ago, Running said, and China appears to be turning a corner.

China remained in the Paris Accord.

“We’re seeing some tangible, early signs of slowing down carbon emissions,” Running said. “But if we don’t quit burning coal, nothing else we do matters. It’s as simple as that.”